PhD thesis: Foundations of Industrial Cybersecurity Education and Training

In my last post I told a very short version of my relationship with ISU’s industrial cybersecurity program. Here I’ll address the second motivating factor for a shift in professional direction: a goal I set for myself in 2005 of obtaining a PhD.

In 2016, I told Corey Schou, who had invited me to return to ISU, “I am willing to make a change; and I have two goals: first is to create the world’s best industrial cybersecurity degree program, and second is to obtain a PhD.”

Corey said “Great! I’ll introduce you to one of the best PhD supervisors I know”, and soon I was engaging with Jill Slay — then at La Trobe University in Melbourne.

Jill happens to be one of the world’s leading experts in cybersecurity education. She was co-chair of the international advisory board of the CSEC-17 project that formally established cybersecurity as an academic discipline.

My friends with PhDs had told me that the best thing you can do is find an outstanding supervisor – someone who knows the space, has confidence in your capabilities, and can provide the right level of support, without being overbearing.

Jill was all that plus the sincere belief in the value of each individual. She personifies the power of careful, critical thought. Each time my work hit a roadblock, she expressed confidence and optimism in me and the work I had undertaken.

How did I have time to do the PhD work while simultaneously building industrial cybersecurity degree program at ISU?

Well, I chose the thesis topic “Foundations of Industrial Cybersecurity Education and Training”. So, there was natural and even necessary congruence. In fact, I don’t think I could have built the program without doing the PhD nor done the PhD without actually building the program, because building something right takes time and critical thought; it takes understanding what others have done before, and determining what needs to be done now.

I am pleased to report that in December 2021, The office of graduate research at the School of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences at La Trobe University accepted my PhD thesis.

You can find the thesis at this link in case you’re interested.

It is dense, but makes several important contributions to the field:

- Clarification of differences between industrial cybersecurity and common cybersecurity for use in guiding education and training

- Comprehensive review of current state of industrial cybersecurity education and training guidance documents/efforts

- Proposed workforce development framework for industrial cybersecurity

- Archetype industrial cybersecurity job roles

- Knowledge categories, topics and justifications

- NSA CAE-style knowledge unit for industrial control systems

- Key tasks for each archetype role

- Leverage point for future standard development

- Historic documentation of process used to create the world’s first cybersecurity education and training standards

As you can tell, I am very thankful to Dr. Corey Schou and Dr. Jill Slay. I also need to thank La Trobe University for the full tuition graduate scholarship. I thank the INL, especially Eleanor Taylor, Wayne Austad, Zach Tudor, Shane Stailey, and for always asking “what can we do to help?” and then providing the help! I also thank Dr. Diana Burley of American University for her thoughtful examination of the thesis — which helped me keep the focus appropriately on “foundations”.

I really do think the work makes some strong initial steps towards establishing the foundation; and, I acknowledge that we still have a long way to go!

ISU’s Industrial Cybersecurity Program and Me

In 2017 I made a significant professional and personal change of course. I was working as the Director of Industrial Control Systems at FireEye’s threat intelligence team. We had a great team, and had produced some compelling intelligence products.

But, I could see that critical infrastructure and industrial control systems was not on the list of important priorities for the company. I did not live in the San Jose or Washington, DC areas — which meant that my access to decision makers was only occasional.

I had been invited by Dr. Corey Schou, under whom I had studied previously, to teach one night a week in ISU’s newly created Cyber-Physical Security program. I was affiliate faculty. I viewed it as my chance to give back a little. It was a low-pressure situation. We only had three students signed up. It was probably best described as an experiment on both the University’s part and mine.

Through the process I recognized that I really enjoyed teaching. Students engaged with the subject matter. And when I walked through the hands-on educational laboratories in the ESTEC building, I realized there was a great opportunity to make something special — to build the next generation of industrial cybersecurity defenders — to create the program I wished I would have been a part of.

So, at the end of a year of teaching pro bono, I decided — let’s do this full time. It was a major change in many ways.

I found the ESTEC department amazing. Instructors have a mix of degrees — from AAS to MS. The requirement to teach was not academic credentials, but real world experience. These are the practical, “get it done people”, in contrast to the “let’s think about how we might go about his if we never had to actually do it” people (said somewhat tongue-in-cheek).

Perhaps most impressively, every one in my department was focused — entirely focused — on the students. These students would leave their various programs with a two-year degree making between 55 and 70 thousand dollars a year. Placement near 100%. It really is a neat place to be. And they have been very supportive of my vision and efforts.

We changed the program name to Industrial Cybersecurity Engineering Technology. We changed course names. We pushed a BAS pathway through the system so that students from a broad variety of Engineering Technology courses could have a clear pathway to bachelor degree that included layering cybersecurity on top of their previous hands-on experience. This last change has allowed students with Engineering Technology degrees in Instrumentation, Electrical, Mechanical, Nuclear Operations and On-site Diesel power to come through the program.

While we started with a heavy reliance on several adjunct faculty members (who had fantastic cybersecurity experience but no industrial cybersecurity experience), I worked my way through the course offerings, eventually authoring the following courses:

- ESET 0181 IT-OT Fundamentals

- CYBR 3383 Security Design for Cyber-Physical Systems

- CYBR 3384 Risk Management for Cyber-Physical Systems

- CYBR 4481 Critical Infrastructure Defense

- CYBR 4487 Professional Development & Certification

- CYBR 4489 Capstone

- ESET 4499 Current Intelligence Practicum

I have to admit that I have never worked harder. My previous efforts at entrepreneurship, as an expert analyst, and as a team manager were engaging and fulfilling, but do not compare with the breadth of competencies (beyond teaching) I have (attempted to?) developed as an instructor and program coordinator. For example:

- Helping administrators accurately understand the cybersecurity space

- Collaborating with peers from other departments on curriculum

- Recruiting students into the program

- Coordinating access to instructional space

- Ensuring students with disabilities have every opportunity to succeed

- Building and running an advisory committee of employers

In the end, it is very rewarding to see students become excited, work hard, and obtain great employment helping secure our critical infrastructure; but, it is no wonder that it is challenging to find, create, and retain good instructors in such an important, emerging field. I hope we are preparing the way!

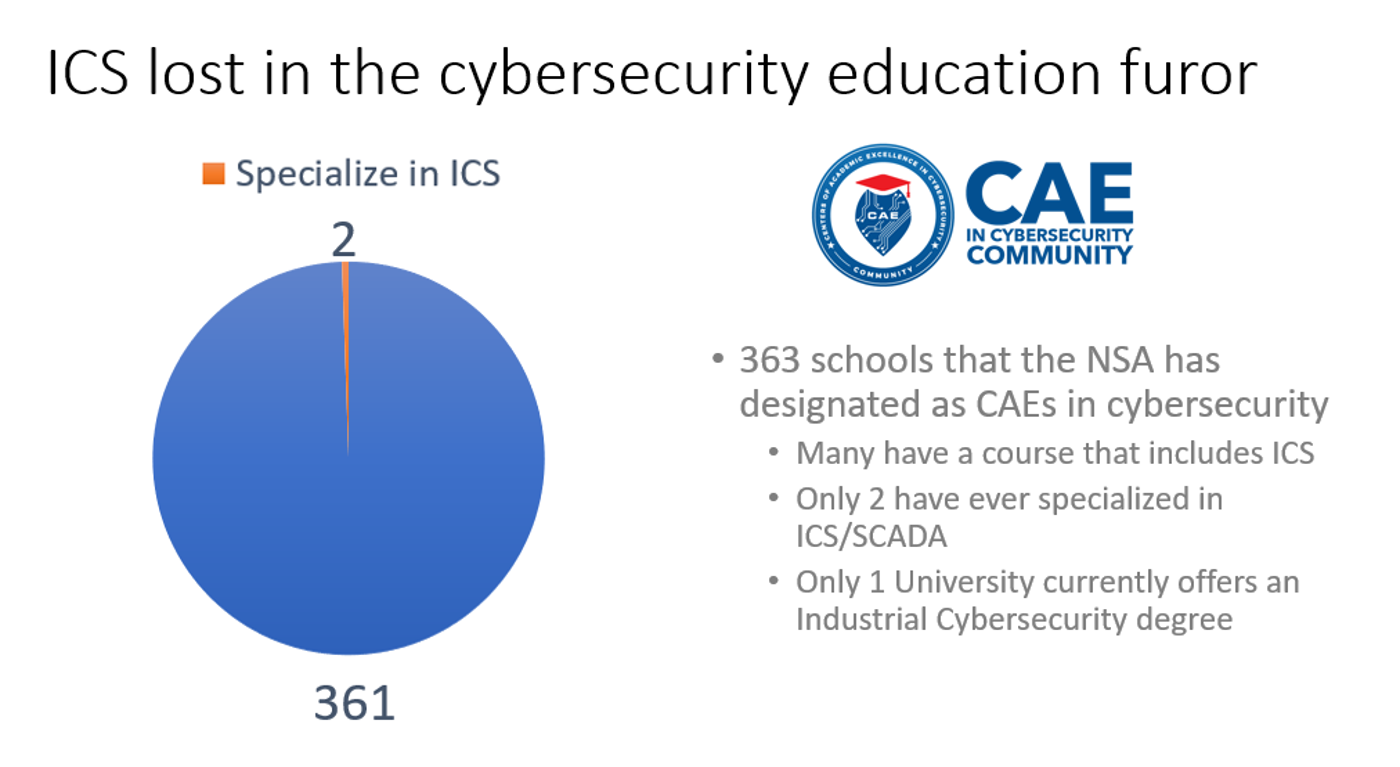

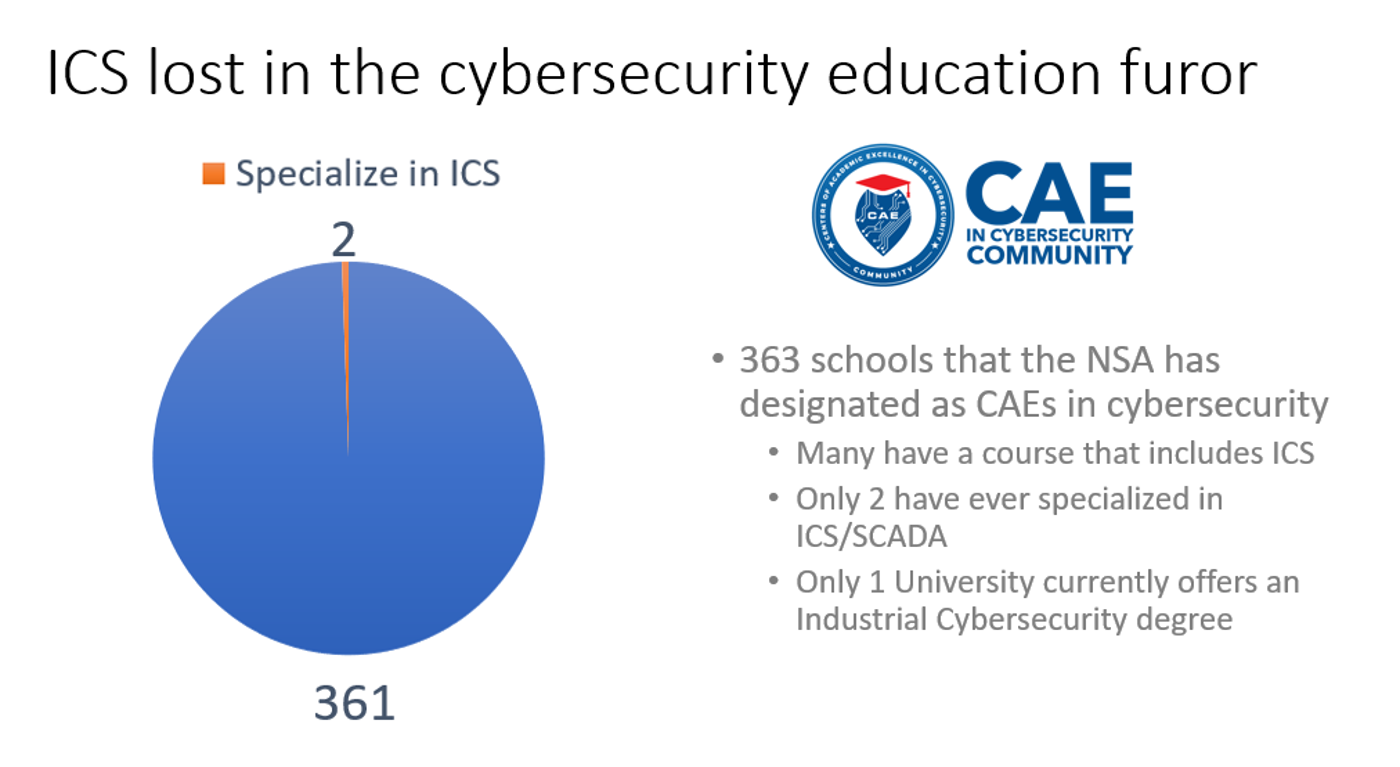

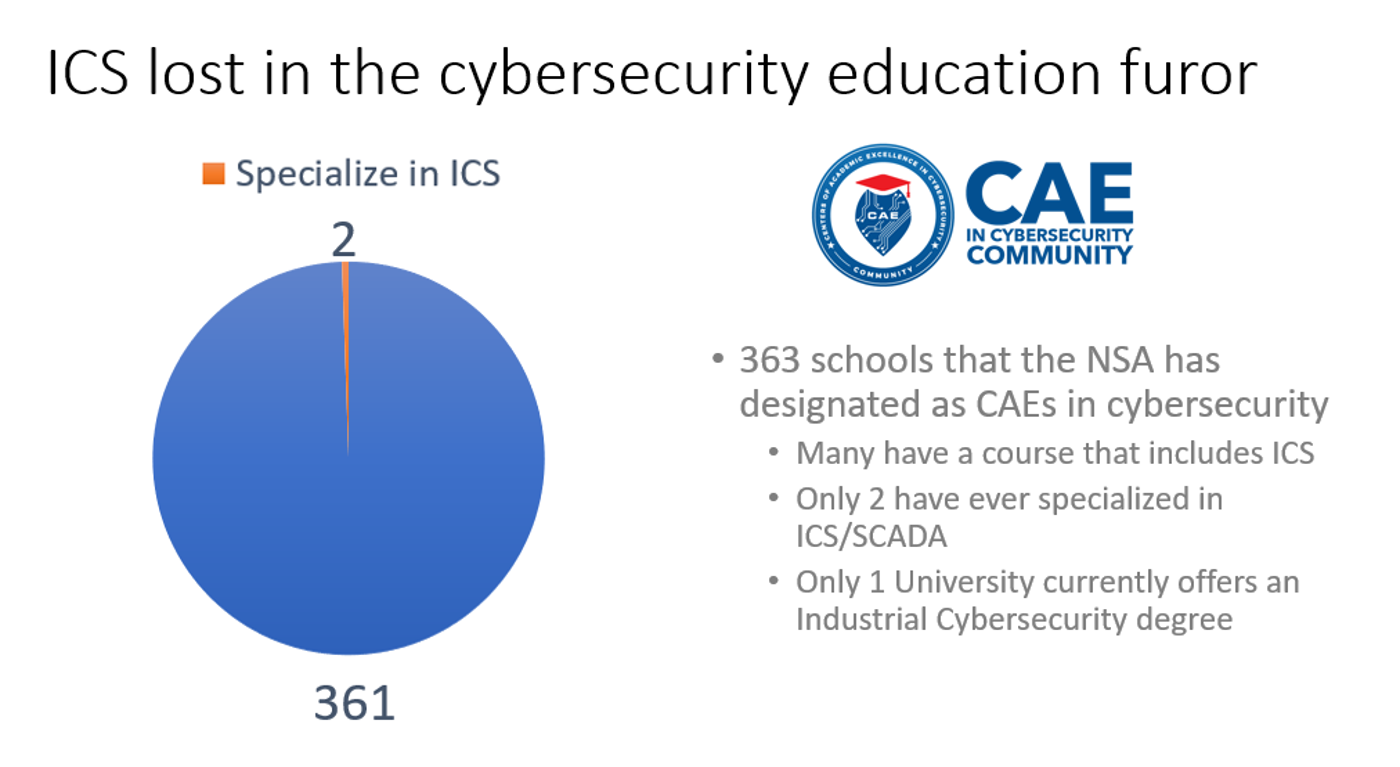

ICS lost in the cybersecurity education furor

My work at ISU (in collaboration with INL and LaTrobe University) has not just been about developing a single Industrial Cybersecurity program — it has really been about addressing a critical need that has been overlooked — that is the need to intentionally and systematically develop an industrial cybersecurity workforce.

I know the statement “critical need that has been overlooked” will meet with opposition — and that some who have reviewed my work not only disbelieve the claim, but find it offensive. There are several reasons for this disagreement, and maybe I’ll discuss them in a later post, but here’s a slide that I think summarizes the current state of affairs:

Yes, there are bright spots at a variety of schools, including University of Houston, Purdue, Everett CC, and others (along with ISU). But the vast majority of the efforts I see focus on adding some ICS content into programs that create traditional cybersecurity professionals and researchers. My observation is that from a strategic point of view, such an approach will be insufficient to securely design, build, operate and maintain critical infrastructures in the age of digitization.

Maybe we don’t just need centers of academic excellence for this space. Maybe we need centers of engineering excellence!

Student Tour at Driscoll Fresh Pack

One of the most exciting things about ISU’s Industrial Cybersecurity program is the tours our students get to take. Last week we visited the Driscoll fresh pack plant.

If you are wondering what “fresh pack” means, you might not be from Idaho — it means fresh potatoes!

According to the foreman who gave us the tour, laborers are hard to come by, and automation has helped make up the difference.

Potatoes arrive in trucks (from storage cellars) to be washed and polished. Sorters send the potatoes down alternate tracks to be boxed or bagged by size as a variety of marketing options for different brands.

Students get to see how the ideas of safety, power distribution, and motor control come together to make the plant run.

My favorite part? Probably the vision systems that identify “strange potatoes” and flick them onto alternate conveyor, where they end up as processed products (think dehydrated mash) rather than fresh products.

More on designing CCE into curricula

One of the neat things we have done in our Critical Infrastructure Defense class is incorporate the CCE methodology. The training materials created by the INL focus on two fictitious scenarios: Stinky Cheese — a Montana-based diary operation, and Baltavia — based roughly on the Ukraine power outages.

The materials allow learners to have some hand-holding with Stinky Cheese, and then a bit more freedom with Baltavia. I think it was a nice approach.

The next step, of course, is for participants to carry out the methodology on real systems. Our students don’t have that quite yet (they are students). So we have come up with set of 16 applied learning activities, as can be seen in the table below. These are in various stages of completion.

| CCE Phase | Activity |

| 1 | Build critical infrastructure sector taxonomy and infographic |

| 1 | Identify high consequence event (HCE) for chosen sector |

| 2 | Conduct notional system of systems analysis (SOSA) for chosen HCE with real artifacts |

| 2 | Conduct SOSA & system description for heat exchanger skid (perfect knowledge) |

| 3 | Break down and document PLC components |

| 3 | Create targeting portfolio for HCE |

| 3 | Develop initial Concept of Operations to cause HCE |

| 3 | Conduct Process Hazards Assessment for heat exchanger skid |

| 3 | Conduct hackability analysis for heat exchanger skid |

| 4 | Identify fail-safe for heat exchanger skid |

| 3 | Conduct Process Hazards Assessment for flow control trainers |

| 4 | Conduct hackability analysis for flow control trainers |

| 4 | Identify fail-safes for flow control trainers |

| 4 | Describe feasibility of recommended fail-safe for flow control trainer |

| 4 | Implement non-hackable fail-safe for flow control trainer |

| 4 | Describe an early warning system for identified HCE |

I feel like CCE is a little light on both phase 3 and phase 4. Phase 3 probably because there is concern about teaching attack-related concepts, and Phase 4 because, well, I don’t know why. But, you can see that those are the areas on which we are really trying to focus.

For the activities in phase 3 and 4, we are supplementing with the ISA Security PHA methodology and book. Maybe I’ll discuss that another day!

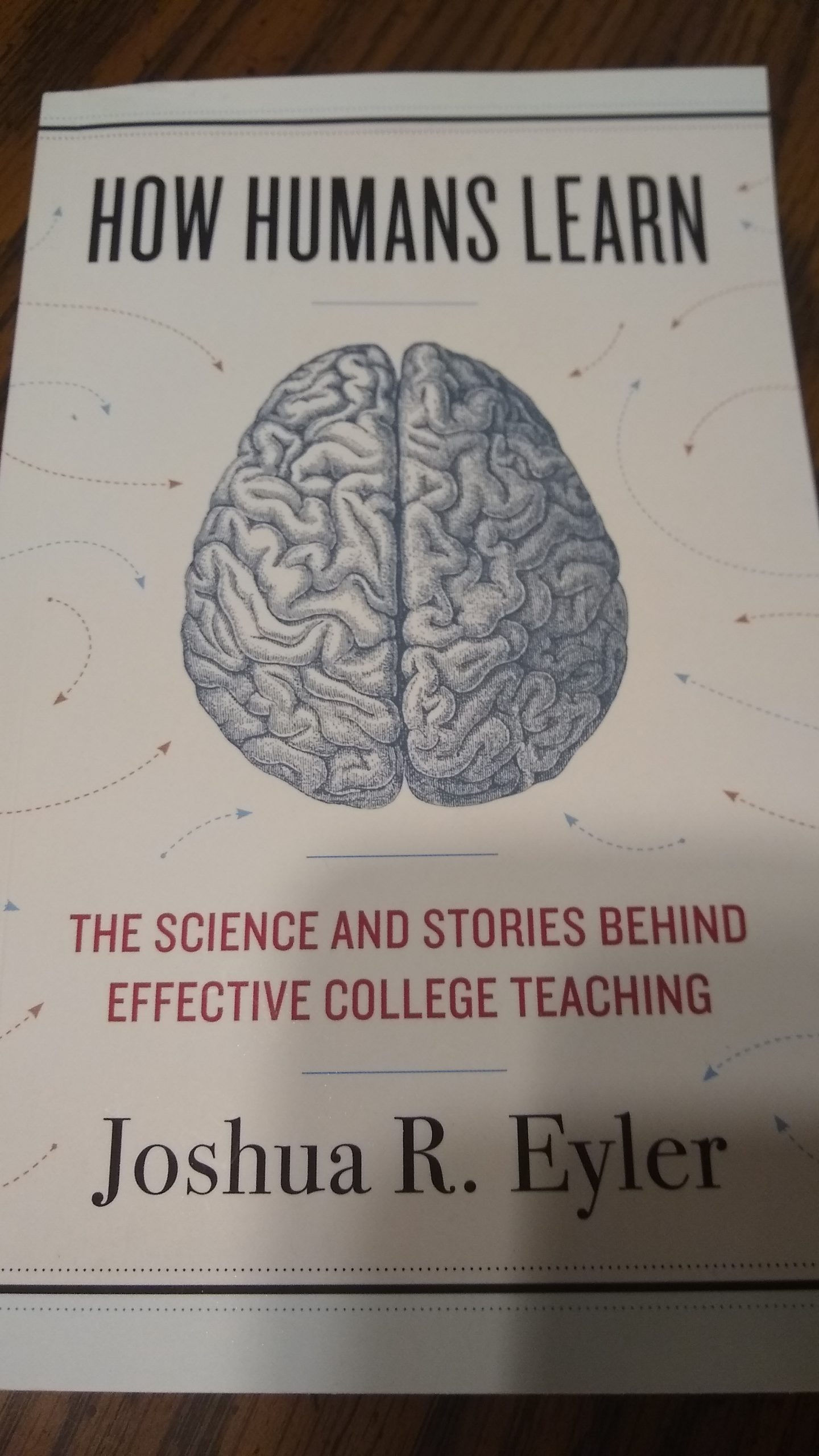

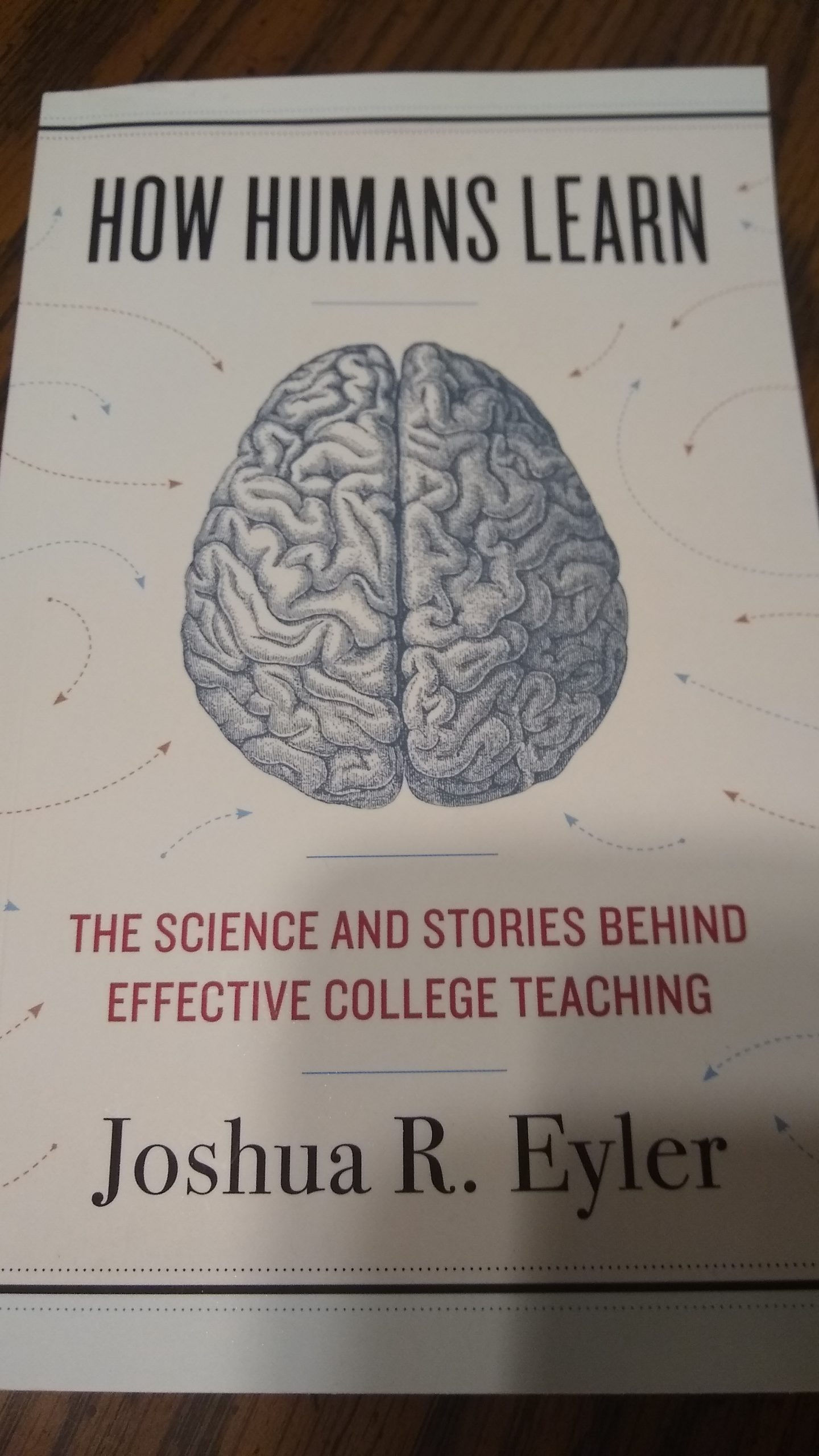

How Humans Learn

I started reading the book “How humans learn” by Joshua Eyler. It’s billed as an idea book for college teachers. Being as I am a college teacher, and I like ideas about teaching — I have not been disappointed.

The first chapter deals with Curiosity. Humans learn because they are innately curious: humans come pre-programmed to learn.

Unfortunately, as Eyler explains (citing the research of others), high-stakes learning teaches humans to learn for reasons other than curiosity. “O wow” I thought, “that sounds exactly like my experience as a young student!”

Eyler suggests designing courses around key questions — so that instead of telling a student what they are expected to learn (which could rob them of the excitement and satisfaction of learning) the entire course is framed as a journey of discovery for the student.

I can see great benefits *IF* students will truly invest in it. But, because I teach college students, I have to counteract students who have already been rewarded for suppressing their natural curiosity!

Nevertheless, I have identified the following (work-in-progress) overarching questions for several of the courses I am teaching this semester:

* ESET 181 IT-OT Fundamentals: How are computers used to control critical the physical real world?

* ESET 4481 Critical Infrastructure Defense: How can we best defend critical infrastructure industrial control systems from intentional cyber attack?

* ESET 4487 Professional Development and Certification: How do you become a successful industrial cybersecurity professional?

These now feature prominently at the top of each course page. I have been referring back to them periodically as I interact with students, lecture, and lead discussions. I already like the feeling of congruence and direction it gives me and them.

Steam Plant Tour

I accompanied our students on a tour of the University steam plant. The plant creates the steam used to heat the buildings on campus. It was a great tour — one of several our students take during their time with us.

Because it is a boiler, with fantastic explosive potential, it is built with thick walls and a thin roof — to explode up — rather than out — limiting potential loss of life. Tour guide/operator waits till students are standing right next to the boiler to tell them that!

From the control room the operators have a view of the key pressures. Cold city water in, steam out.

HMI display of the boiler. Automated control happens in this enclosure. If anything goes wrong, close off natural gas valve in, and open valve for incoming water. Operator advice: “You can look at the panel, please don’t bump it though.”

Softener system. Don’t run out of salt. Manual pH measurement station.

We use radio tour-guide head sets — very helpful in noisy environments. Great instructor. Awesome students.

Whatcha readin?

So, I’ve been reading and listening quite a bit lately. A while ago, a friend of mine sent me a copy of “The Great Game” by Peter Hopkirk. Very engaging, and certainly on point given the recent US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

The book is named after a core idea in Kipling’s “Kim” — a book about a young anglo-Indian boy who becomes a spy. So, midway through “The Great Game” I decided to pause while I took up “Kim”. For anyone interested in spycraft, Kim is a fun read/listen (and it is a book where voice talent makes a big difference!).

Kipling – 1891

I was most impressed with Kipling’s effort (ability) to represent the perspectives and manners of cultures, ages, and gender. I love that aspect of “intelligence” — though I don’t always love how it is applied by intelligence services.

I also appreciate the deeper messages of the unity of mankind and duty to God that generally pervade Kipling’s work.

And, I found a couple of teaching-related treasures in “Kim”:

The first is a scene where Mahabub Ali, a horse-trader and spy, criticizes the madrasa — the school — where Kim is receiving his formal education. He says “Son, I am weary of that madrasa, where they take the best years of a man to teach him what he can only learn on the road. The folly of the sahibs has neither top nor bottom. And God, he knows, we need men more and more in the game”.

I couldn’t help but feel a little bit the same way about my own formal education. I wish it had a stronger applied focus. My favorite experiences occurred where I was applying my learning to my concurrent employment. And we do need men and women more and more in protecting our critical infrastructure systems. We need to prepare them efficiently and effectively.

The second is a scene where Kim and another young man are learning to expand their powers of observation. They are shown a tray of curiosities for a few seconds, and then told to describe the items on the tray, which they can no longer see. At first, Kim’s performance lags far behind a younger boy, but he learns to increase his power of observation.

I couldn’t help but agree wholeheartedly with the importance of quickly committing key information to memory, careful attention to detail, and the value of relevant practice. These can be reinforced by making the exercise a friendly contest — gamification.

Industrial Cybersecurity Workforce Development Community of Practice

In August of 2020, we got together with our friends from the INL for a brainstorming session at ESTEC in Pocatello. We asked ourselves, “What could we do together, that would help us get participation and raise visibility for industrial cybersecurity education?”

We decided to launch a virtual workshop — low cost — low risk — high potential payoff. We invited some great people in government and academia, and held a day-long workshop. Over 100 people attended.

To keep the momentum going, we decided to name it the “Industrial Cybersecurity Workforce Development Community of Practice” or ICSCOP for short. We divided into subgroups. We held monthly meetings. We did additional workshops in May and November 2021. Participants from all over the country have attended the meetings. ISA has been a strong supporter. NIST NICE leadership has also been a significant collaborator as they try to add ICS coverage into the NICE framework. Based on joint interests, Ida Ngambeki of Purdue and I wrote a paper together for the CISSE conference.

We are excited about the future. Check out this great article about the ICSCOP that ran in the NICE winter e-newsletter: https://www.nist.gov/itl/applied-cybersecurity/nice/nice-enewsletter-winter-2021-22-government-spotlight.

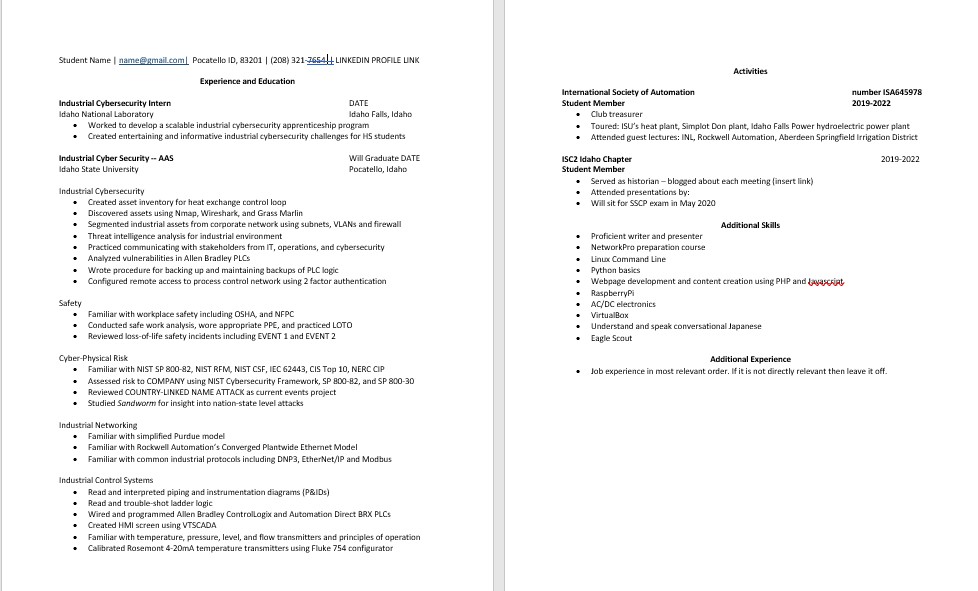

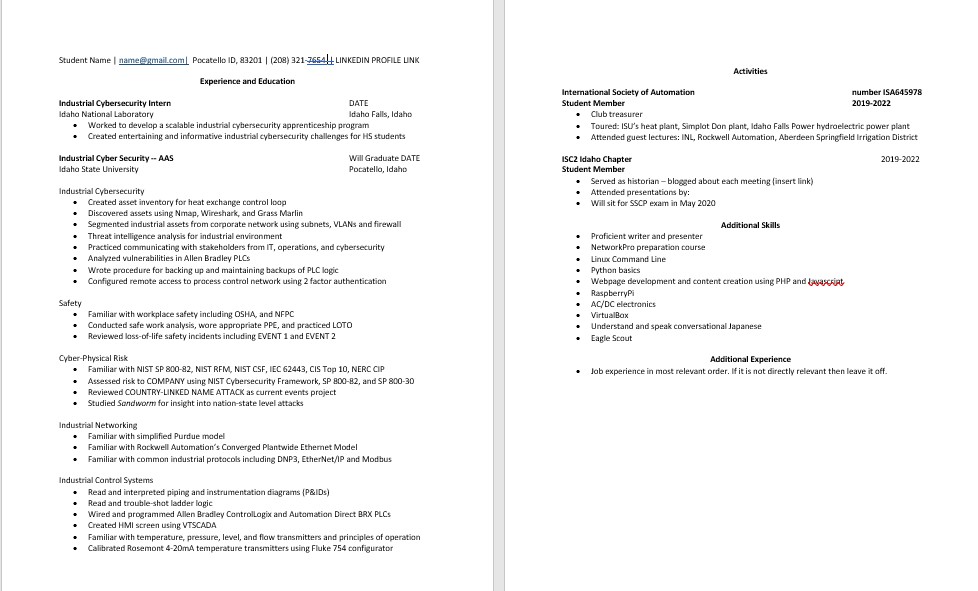

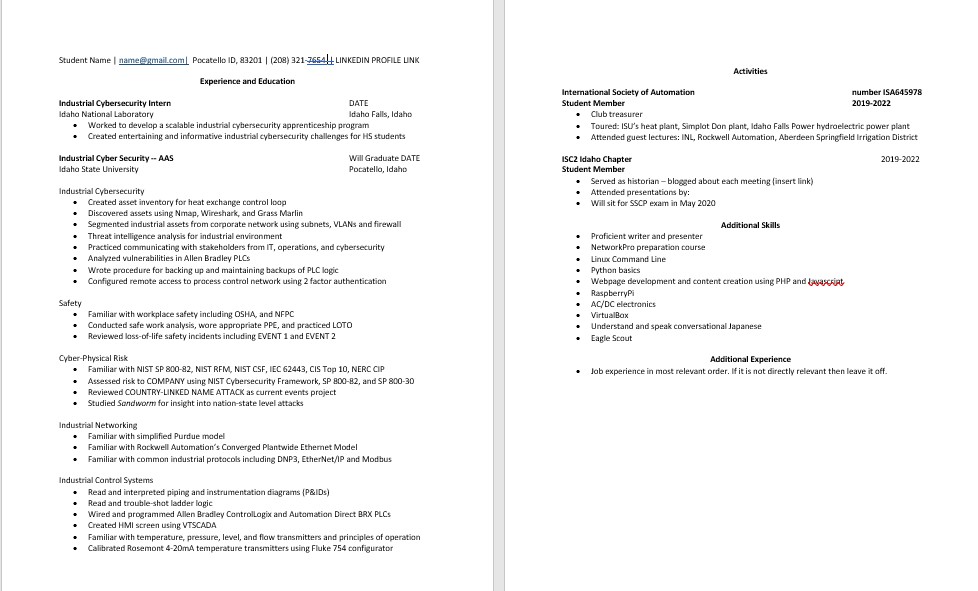

Resume preparation for industrial cybersecurity students

So, students in our professional development and certification class have been preparing their resumes. For students without much professional experience, this is significant challenge.

Fortunately, our Industrial Cybersecurity students have a lot of learning experiences to draw from. I provide them with a prototype resume that includes statements of things they have done during the program. They can select and tailor statements to their projects and interests, and to closely match the job description and requirements.

I try to put them in the mind-set of the HR lead and the hiring manager.

I explain that HR lead is the “pre-screener” — eliminating those who are obviously not qualified. The hiring manager will then sort the resumes into yes and no piles. In some cases this is a diligent process. In some cases, its a “feel” thing. In some cases this is a committee decision.

“Yes” pile resumes will qualify for a cover letter read, if cover letters are part of the process. Some organizations will administer a test of sorts. Based on the results, three to five candidates will be chosen for an interview. Two candidates will be called back for a second interview.

I think the most effective way to put students in the mindset of the HR lead and hiring manager is to expose them to a bunch of resumes. So, I have students bring several copies of their resume, which they share with classmates (I ask them to remove their names so that they don’t get distracted by that point).

Then we do a drill where students take five seconds to consume each resume and make a mental “yes” or “no” decision. While five seconds may be sightly on the short side, it gets the point across.