This is the third post in a three-post series about the Centers of Academic Excellence (CAEs) In Cybersecurity. Previous posts dealt with

1. Increasing number of CAE-designated institutions.

2. Mapping to roles to your program of study

This leads us to:

3. Incorporating competency statements

To me, this is the most theoretically problematic of the current CAE directions. I’m going to tell you why.

As background, you need to understand that the latest (draft) guidance for achieving CAE designation requires not only aligning your program to three roles but also identifying and listing 10 “competency statements”.

The word “competency” occurs some 25 times in the latest draft requirements. It says, “competency is the ability of the individual to complete a task in the context of a work role.” The document further explains “A focus on competency provides an effective bridge between the students’ educational experiences and the workplace, and competencies connect students’ learning (through their academic program, co-curricular, and extra-curricular activities) to cybersecurity work roles.”

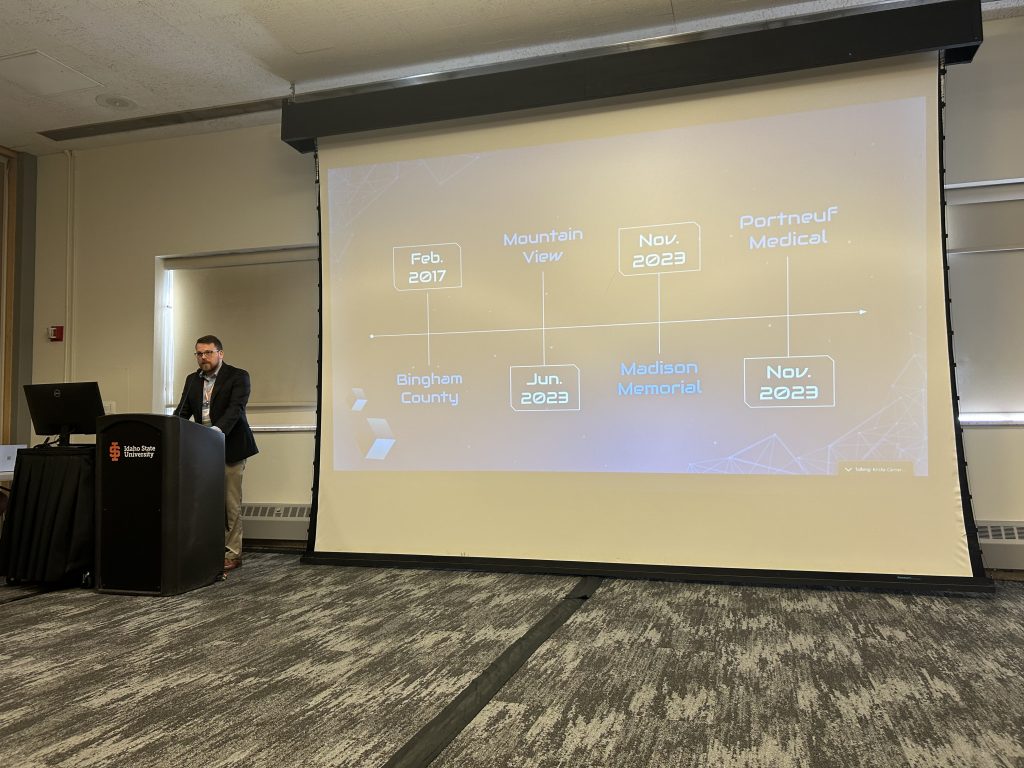

I like/love/support the idea of intentionally linking what a student learns in a cybersecurity program of study with what the workforce requires. While I am PhD, I am also a state of Idaho certified post-secondary Career and Technical Education (CTE) instructor. I endorse hands-on, applied learning as a necessary component of a quality program.

So why do I find this requirement problematic?

In the end it is burdensome, confusing, limiting, and ultimately entirely necessary.

First: burdensome.

If you look at the roles frameworks (NICE or DCWF), you see that every work role has associated task, knowledge, and skill statements.

For example, the Program Management Work Role (OG-WRL-010) has about 40 Tasks, such as:

T1155: Develop risk, compliance, and assurance measurement strategies

T1227: Manage cybersecurity budget, staffing, and contracting

T1259: Identify opportunities for new and improved business process solutions

As explained in my previous post, the proposed designation requirements already ask programs to choose to align with three cybersecurity work roles.

Where the work roles described in NICE or DCWF already have task, knowledge, and skill (TKS) statements, why ask institutions to write their own statements? Isn’t the intent of TKS statements to represent what the employer wants and needs?

It would seem simpler to just ask the institutions to show how their learning activities align to the tasks for the roles they selected.

Second: confusing

We have a terminology soup going on here.

The definition and description of “competency” within the proposed CAE designation requirements differs substantially from the way the term is used and defined in the NIST NICE documentation (from which the roles are chosen). The actual NIST NICE framework includes an entire section on competencies (Section 3.3), which it defines as “a mechanism for organizations to assess learners”.

But the team at NIST appears to have not liked that definition in the long run, because they omitted it entirely from the NICE framework glossary of terms.

In the glossary, the NIST NICE team opted instead for “capability”, which is, “a person’s potential to accomplish something.” That sounds a lot like the definition of “competency” from the draft CAE designation requirements, which was “the ability of the individual to complete a task…”

And to complicate things more, the NICE glossary includes the term “Competency area”, which it defines as “a cluster of related Knowledge and Skill statements that correlates with one’s capability to perform Tasks in a particular domain. Competency Areas can help learners discover areas of interest, inform career planning and development, identify gaps for knowledge and skills development, and provide a means of assessing or demonstrating a learner’s capabilities in the domain.”

In addition to “competency” the CAE designation guidance also refers to:

- “Program-level learning outcomes”, which are “a description of what graduates should know or be able to do upon completion of the program of study… Each Program of Study should have multiple Program-Level learning outcomes that are consistent with the needs of the program’s focus and various constituencies.”

- “KU outcomes”, which are “a specific assessment of a concept associated with a particular KU”, and

- “Course outcomes”, which are “expectations that the academic institution and the PoS is anticipating students to be able to demonstrate when completing a course.”

Moreover, for institutions seeking ABET cybersecurity accreditation, ABET requires establishment and periodic review of “program educational objectives”, and “student outcomes”:

- Program educational objectives are “the broad statements that describe the career and professional accomplishments that the program is preparing graduates to achieve” – such as within three to five years of graduation.

- Student outcomes (sometimes called Student Learning Outcomes) are “statements that describe what students are expected to know or be able to do by the time they complete an academic program.”

Finally, as a course author and instructor, I like to take it deeper, authoring learning objectives for each module, each class period, and each learning activity.

Writing good objectives is important because it’s a reminder of what the instructor intends to accomplish. Objectives should be carefully considered and reviewed. I find myself tweaking objectives at the learning activity level quite frequently, especially when I introduce a new assignment or change an element of an assignment.

I have been at this for eight years. I have achieved both CAE program designation and ABET accreditation. I have placed my students in some of the best cybersecurity organizations in the country. Sometimes I’m left wondering: how can anyone trying to align with the CAE designation requirements, ABET accreditation criteria, and the NICE framework, keep all of this straight?

Third, limiting

The third reason I find the proposed competency requirement problematic is the document dictates a single construct for writing competency statements:

“Every competency can be described through the Essential Elements (ABCDE) framework. The five essential elements to every competency are the actor, behavior (task), context, degree, and employability”.

Mager used the ABCD framework as a nice mnemonic device, but each of the ABCD terms have other established meanings in workforce and educational literature.

| CAE concept (adapted from Mager) | Common concept |

| A: Actor (Audience) | Employee/Work Role |

| B: Behavior | Task or Activity |

| C: Context (Conditions) | Context |

| D: Degree | Proficiency/pass mark |

| E: Employability | Essential professional skills |

A: Actor. The Competency in Cybersecurity Education Handbook indicates this is the student. In my mind, the actor here should be an entry level version of the selected role.

B: Behavior. This is really the “task” itself. I think there are better uses of the word “behavior”. For example, a behavior can describe the way a person completes a task and the reasons they do it that way. Expert behaviors differ from novice behaviors. Equating behaviors and tasks is limiting.

C. Conditions. This describes the resources and tools and tools to complete the task. I think of this much more broadly: it should include the antecedent events, the relationships among individuals, sights and sounds of the place work is performed, the tools available for completing the work, and the expected format of the deliverable (if a deliverable is expected).

D. Degree. How well the actor performs. To me, this equates much more clearly to proficiency. This can be defined in terms of accuracy, speed, completeness, etc.

E. Employability. What basic employability skills are required/displayed. This is an extension to the Mager ABCD concept. I consider these as the non-technical component of a task. “Communicating clearly and respectfully with customers” could be an example. Instructors really have to work hard to make sure they are including and emphasizing these skills.

I think the ABCDE mnemonic could be helpful if you have little previous experience writing learning objectives. But it also introduces another layer of complexity for instructors to master. Is it the place of the CAE to teach how to write educational objectives? Or should this be left to programs serving the “Cybersecurity Instruction” work role?

I would prefer if the guidance recognized that there are several good methods for writing competency statements. The IEEE Recommended Practice for Writing Competencies (2022) identifies three useful models: 1) Context, Action Result (CAR); 2) Situation, Task, Action, Result (STAR); 3) Action, Instruction, Result (AIR). It would be nice if the designation guidance had simply pointed users to several resources such as the IEEE recommended practice or Mager’s book on Preparing Educational Objectives.

Finally, entirely necessary.

It seems to me that the CAE criteria group really wants to ensure that CAE designation means that students are being prepared effectively for real-world cybersecurity careers – which I enthusiastically support.

The challenge is that to accomplish that goal, the proposed requirements have bolted the idea of “roles” and “competencies” onto the existing academic “knowledge unit” approach.

This seems awkward and duplicative. I think we should stick with one or the other — but not both.

In my opinion, it should be quite simple to jettison the academic “knowledge unit” approach in favor of the applied approach. All the program-level learning outcomes should align to the roles. Then replace the KU outcomes with Tasks/Competency statements that the NICE/DCWF framework already include.

Courses can still be structured around knowledge/topics, because the knowledge can be mapped to support specific roles and tasks (the NICE framework has already done work on that mapping).

Is my view too simplistic?