I’ve been very busy the past month writing, writing, writing.

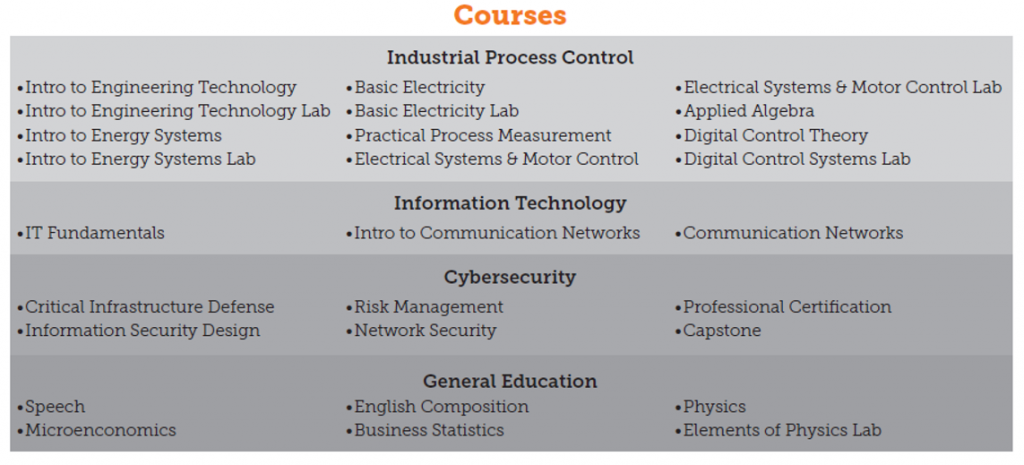

You will now find a section entitled “Papers” within the site menu. This is where I will post the papers I’ve written related to the topic of industrial cybersecurity education. I’ll post the manuscript versions there, and then replace them with the published versions. This also allows paper reviewers to find manuscripts to which I refer (if self-references are allowed in copies submitted for review, of course).

The first papers I’ve posted describe the need for industrial cybersecurity education as a well-defined sub discipline. They examine efforts to establish industrial cybersecurity education and training standards 1) in the USA, and 2) in the world. They also provide detailed recommendations to improve the situation.

As you might expect with most academic literature, the papers are a bit dense; but, I’ve tried to ensure they flow well. I will cover elements of the content in later posts.

In the end, analysis finds that current standards fall short in three ways:

- They were created without consideration for the unique needs of industrial control systems

- They lack thorough development

- They do not account for the career paths of industrial professionals

So far, I think I agree with several principal points:

So far, I think I agree with several principal points:

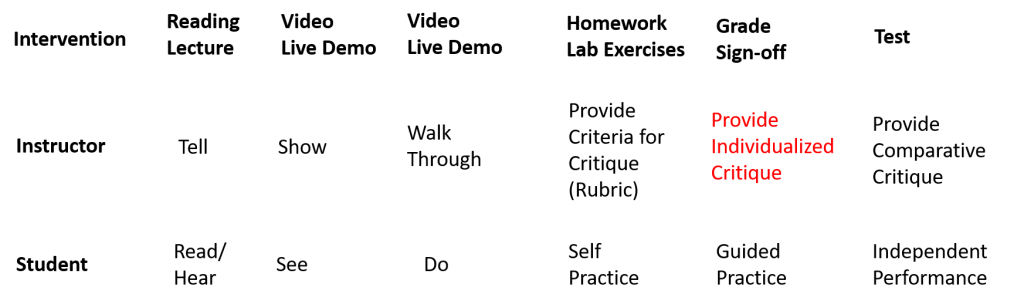

As COVID-19 has moved our in-person class to an online format, I decided to move the Sandworm discussion online too.

As COVID-19 has moved our in-person class to an online format, I decided to move the Sandworm discussion online too.