Incorporating Competency Statements

This is the third post in a three-post series about the Centers of Academic Excellence (CAEs) In Cybersecurity. Previous posts dealt with

1. Increasing number of CAE-designated institutions.

2. Mapping to roles to your program of study

This leads us to:

3. Incorporating competency statements

To me, this is the most theoretically problematic of the current CAE directions. I’m going to tell you why.

As background, you need to understand that the latest (draft) guidance for achieving CAE designation requires not only aligning your program to three roles but also identifying and listing 10 “competency statements”.

The word “competency” occurs some 25 times in the latest draft requirements. It says, “competency is the ability of the individual to complete a task in the context of a work role.” The document further explains “A focus on competency provides an effective bridge between the students’ educational experiences and the workplace, and competencies connect students’ learning (through their academic program, co-curricular, and extra-curricular activities) to cybersecurity work roles.”

I like/love/support the idea of intentionally linking what a student learns in a cybersecurity program of study with what the workforce requires. While I am PhD, I am also a state of Idaho certified post-secondary Career and Technical Education (CTE) instructor. I endorse hands-on, applied learning as a necessary component of a quality program.

So why do I find this requirement problematic?

In the end it is burdensome, confusing, limiting, and ultimately entirely necessary.

First: burdensome.

If you look at the roles frameworks (NICE or DCWF), you see that every work role has associated task, knowledge, and skill statements.

For example, the Program Management Work Role (OG-WRL-010) has about 40 Tasks, such as:

T1155: Develop risk, compliance, and assurance measurement strategies

T1227: Manage cybersecurity budget, staffing, and contracting

T1259: Identify opportunities for new and improved business process solutions

As explained in my previous post, the proposed designation requirements already ask programs to choose to align with three cybersecurity work roles.

Where the work roles described in NICE or DCWF already have task, knowledge, and skill (TKS) statements, why ask institutions to write their own statements? Isn’t the intent of TKS statements to represent what the employer wants and needs?

It would seem simpler to just ask the institutions to show how their learning activities align to the tasks for the roles they selected.

Second: confusing

We have a terminology soup going on here.

The definition and description of “competency” within the proposed CAE designation requirements differs substantially from the way the term is used and defined in the NIST NICE documentation (from which the roles are chosen). The actual NIST NICE framework includes an entire section on competencies (Section 3.3), which it defines as “a mechanism for organizations to assess learners”.

But the team at NIST appears to have not liked that definition in the long run, because they omitted it entirely from the NICE framework glossary of terms.

In the glossary, the NIST NICE team opted instead for “capability”, which is, “a person’s potential to accomplish something.” That sounds a lot like the definition of “competency” from the draft CAE designation requirements, which was “the ability of the individual to complete a task…”

And to complicate things more, the NICE glossary includes the term “Competency area”, which it defines as “a cluster of related Knowledge and Skill statements that correlates with one’s capability to perform Tasks in a particular domain. Competency Areas can help learners discover areas of interest, inform career planning and development, identify gaps for knowledge and skills development, and provide a means of assessing or demonstrating a learner’s capabilities in the domain.”

In addition to “competency” the CAE designation guidance also refers to:

- “Program-level learning outcomes”, which are “a description of what graduates should know or be able to do upon completion of the program of study… Each Program of Study should have multiple Program-Level learning outcomes that are consistent with the needs of the program’s focus and various constituencies.”

- “KU outcomes”, which are “a specific assessment of a concept associated with a particular KU”, and

- “Course outcomes”, which are “expectations that the academic institution and the PoS is anticipating students to be able to demonstrate when completing a course.”

Moreover, for institutions seeking ABET cybersecurity accreditation, ABET requires establishment and periodic review of “program educational objectives”, and “student outcomes”:

- Program educational objectives are “the broad statements that describe the career and professional accomplishments that the program is preparing graduates to achieve” – such as within three to five years of graduation.

- Student outcomes (sometimes called Student Learning Outcomes) are “statements that describe what students are expected to know or be able to do by the time they complete an academic program.”

Finally, as a course author and instructor, I like to take it deeper, authoring learning objectives for each module, each class period, and each learning activity.

Writing good objectives is important because it’s a reminder of what the instructor intends to accomplish. Objectives should be carefully considered and reviewed. I find myself tweaking objectives at the learning activity level quite frequently, especially when I introduce a new assignment or change an element of an assignment.

I have been at this for eight years. I have achieved both CAE program designation and ABET accreditation. I have placed my students in some of the best cybersecurity organizations in the country. Sometimes I’m left wondering: how can anyone trying to align with the CAE designation requirements, ABET accreditation criteria, and the NICE framework, keep all of this straight?

Third, limiting

The third reason I find the proposed competency requirement problematic is the document dictates a single construct for writing competency statements:

“Every competency can be described through the Essential Elements (ABCDE) framework. The five essential elements to every competency are the actor, behavior (task), context, degree, and employability”.

Mager used the ABCD framework as a nice mnemonic device, but each of the ABCD terms have other established meanings in workforce and educational literature.

| CAE concept (adapted from Mager) | Common concept |

| A: Actor (Audience) | Employee/Work Role |

| B: Behavior | Task or Activity |

| C: Context (Conditions) | Context |

| D: Degree | Proficiency/pass mark |

| E: Employability | Essential professional skills |

A: Actor. The Competency in Cybersecurity Education Handbook indicates this is the student. In my mind, the actor here should be an entry level version of the selected role.

B: Behavior. This is really the “task” itself. I think there are better uses of the word “behavior”. For example, a behavior can describe the way a person completes a task and the reasons they do it that way. Expert behaviors differ from novice behaviors. Equating behaviors and tasks is limiting.

C. Conditions. This describes the resources and tools and tools to complete the task. I think of this much more broadly: it should include the antecedent events, the relationships among individuals, sights and sounds of the place work is performed, the tools available for completing the work, and the expected format of the deliverable (if a deliverable is expected).

D. Degree. How well the actor performs. To me, this equates much more clearly to proficiency. This can be defined in terms of accuracy, speed, completeness, etc.

E. Employability. What basic employability skills are required/displayed. This is an extension to the Mager ABCD concept. I consider these as the non-technical component of a task. “Communicating clearly and respectfully with customers” could be an example. Instructors really have to work hard to make sure they are including and emphasizing these skills.

I think the ABCDE mnemonic could be helpful if you have little previous experience writing learning objectives. But it also introduces another layer of complexity for instructors to master. Is it the place of the CAE to teach how to write educational objectives? Or should this be left to programs serving the “Cybersecurity Instruction” work role?

I would prefer if the guidance recognized that there are several good methods for writing competency statements. The IEEE Recommended Practice for Writing Competencies (2022) identifies three useful models: 1) Context, Action Result (CAR); 2) Situation, Task, Action, Result (STAR); 3) Action, Instruction, Result (AIR). It would be nice if the designation guidance had simply pointed users to several resources such as the IEEE recommended practice or Mager’s book on Preparing Educational Objectives.

Finally, entirely necessary.

It seems to me that the CAE criteria group really wants to ensure that CAE designation means that students are being prepared effectively for real-world cybersecurity careers – which I enthusiastically support.

The challenge is that to accomplish that goal, the proposed requirements have bolted the idea of “roles” and “competencies” onto the existing academic “knowledge unit” approach.

This seems awkward and duplicative. I think we should stick with one or the other — but not both.

In my opinion, it should be quite simple to jettison the academic “knowledge unit” approach in favor of the applied approach. All the program-level learning outcomes should align to the roles. Then replace the KU outcomes with Tasks/Competency statements that the NICE/DCWF framework already include.

Courses can still be structured around knowledge/topics, because the knowledge can be mapped to support specific roles and tasks (the NICE framework has already done work on that mapping).

Is my view too simplistic?

Mapping your School’s Cybersecurity Program to Professional Work Roles

In a previous blog post, I promised to cover three topics related to the development of the NSA CAE community:

1. Increasing number of CAE-designated institutions.

2. Mapping to roles

3. Incorporating competency statements

I covered number one last time. This post is dedicated to 2: Mapping to roles

One of the innovations introduced over the past couple of years in the CAE community is aligning a designated program of study to work Roles. This is now a requirement for new and renewed CAE-designated programs of study.

For CAE-designation purposes, Roles should be chosen from the 52 identified in the NIST NICE framework or the 54 identified in the DOD CWF. (The fact that there are two competing frameworks may befuddle, but I think it is actually not a bad thing – because they have different strengths.)

First, what is a work role?

This is an important question. Its answer seems deceptively simple:

NIST NICE says they are “a way of describing a grouping of work for which someone is responsible or accountable”.

It is important to recognize that work roles are not job titles (though they might sound like, or could in some cases even be job titles) – which is admittedly confusing and non-intuitive. Instead, they are common groupings of tasks, knowledge, and skill statements. Under this system, a single worker can have multiple roles. The image below, taken from the NICE framework describes the relationships.

As I said before, CAE-designation requires CAE institutions to identify three Roles to which their program of study intends to align. Said another way, these are roles for which the program intends to prepare its students.

If you think about this from an employer’s perspective (especially a federal or DoD employer), this should simplify recruiting and hiring: “I look at my hiring needs, you show me what roles your program prepared you to do, and voile, we have a fit”.

I like that idea. Here are my questions and concerns:

- Isn’t “fit” much more complex than work role preparation?

- How exclusive are roles? / Are there natural role clusters?

- Does it make sense to force students into Roles (at 2-year, 4-year, and graduate levels)?

- Are students going to choose programs that match their role interests and aptitudes in the first place?

- Are employers inside and outside the federal government tracking/projecting hiring/demand information for these roles?

- How accurate are those projections?

- Can the projections be shared with the CAEs?

- How difficult is it for an academic institution to change “Roles” to meet new/projected demands?

- Do some roles have more/fewer TKS statements?

- Are some roles more challenging/difficult than others to learn/perform?

- Do some roles pay more/less than others?

- Should that pay information be available to students to help students choose institutions/programs of study?

- Might each role align better to a course than to an entire program of study?

- What qualifies instructors to teach about a certain role?

I believe that these questions can be answered. But I think it will require a significant effort from employers and students as well as educators to achieve the expected or desired value of aligning programs of study to roles.

Now, for the irony. When the CAEs were first stood up in the late 1990s, designation required alignment with the information assurance training standards for national security systems. These standards were based on several roles; namely: System Administrators, Information Systems Security Officers, System Certifiers, and Risk Analysts. These training standards appear to still be in force, though they are no longer used in the CAE designation process.

In about 2014, the CAE community turned away from Roles and towards the idea of knowledge units (KUs). This approach was much more academic than applied: what a student/graduate knew took precedence over the things a graduate was prepared to do. Naturally there is some correlation between knowledge and tasks (and remember that the NICE framework wasn’t released until 2017, and DODCWF was not released until 2023 – so alignment to the breadth of roles was not even a choice). But the irony in aligning to Roles is that everything old is new again.

CAEs – What is Excellence?

From participation in last-week’s symposium, it is clear that CAEs are developing in several significant ways:

- Increasing number of CAE-designated institutions

- Requiring each program to align to recognized cybersecurity roles

- Incorporating competency statements

I am going to dedicate the next several blog posts to these topics. Today I am covering the increasing number of CAE-designated institutions.

Over the 27 years of its existence, the CAE community has grown from just 7 institutions to 467. This is an annual growth rate of 16.84 percent. That is quite impressive. Play that out for another 10 years and we would be looking at about 2,000 CAEs.

According to the US National Center for education statistics, there are 3,931 higher educational institutions in the USA during 2020-2021. So 2,000 would be a 50% penetration rate. Impressive. Will the demand for entry level cybersecurity professionals continue at that pace for the next decade?

The presentations also indicated that currently, 137 of the 467 CAEs are community colleges (~30%). Department of Education reports that in 2020-2021, there were 1,022 community colleges in the USA. If growth were to achieve a total 50% penetration across all IHEs, we would expect much of the CAE growth to come from community colleges.

At the symposium I made some new friends – including several from community colleges. I loved the community college instructors. Those I spoke with had transitioned to teaching from other careers – one from military service, and another from IT. They love teaching – because they know education makes a difference!

My concern with this rate of growth is that instead of developing centers of academic excellence (CAEs), we are developing centers of educational adequacy (CEAs)! Don’t get me wrong: you must pass through adequacy to reach excellence; but, in a situation (10 years from now) where half the schools in the country rely on canned curricula, free lab experiences, and standardized assessments – what should/will excellence look like?

I have given some thought into how I would stay ahead. I won’t give away all the details here and now, but here are some focal points:

- New foundational paradigms

- Transformative experiences

- Cyber-infused interdisciplinary programs of study

- Interpersonal excellence

At the CAE Annual Symposium

This week I am in Charleston at the National Centers of Academic Excellence (CAE) Symposium in Charleston. I am guessing there are around 500 attendees representing the 467 (if I heard correctly) NSA designated CAEs. If you are a CAE, attendance is required.

A little background: NSA stood up the CAEs in 1998. ISU (where I teach) was one of the original 7 CAEs. The Idea was that there was no specialized accreditation for cybersecurity education. NSA awarded the CAE designation to institutions that aligned their curricula with the NSTISS/CNSS 401x training standards.

Becoming a CAE-designated institution requires having a designated program of study (among other requirements).

Institutions can be designated for cyber defense (CD), research (R), and/or cyber operations (CO).

The good:

It is cool to see such a vibrant community of educators. I think there are seven simultaneous tracks at some points. Because the CAE community is growing, there are lots of schools and faculty that are “new”. It is fun to talk with this friendly group. If you’ve been here before, it is good to see faculty friends from other institutions.

When I go to a conference, I find that I enjoy it more if I attend sessions that I know nothing about.

In that attitude, I rather enjoyed the session by Derek Hansen of Brigham Young University about creating a graphic modeling language for cyber attack scenarios. I wouldn’t call it a stroke of sheer genius, but I understood the power in making students express adversarial thinking graphically.

I have students in my Critical Infrastructure Defense class do a deep dive of the Triton attacks against the oil refinery in Saudi Arabia, and use MITRE ATT&CK to describe the techniques used.

I can see that my assignment focuses on one-step-at-a-time, and ultimately ends up in a good bit of text. So asking students to select and arrange graphics would reinforce a wholistic view and the importance of technique sequencing.

I could perceive that complicated attacks might not fit in one graphic. But that’s ok.

Derek’s presentation got me thinking about modeling (languages) in general. Our (mental) models can limit or empower us. I have spent a lot of effort over the past years consuming and contributing to workforce development models. I carefully compared 15 or so cybersecurity workforce development models for my PhD thesis (chapter 7). None of these natively used a graphical component. I wonder whether a graphical approach would be beneficial there…

The not-so-good:

It’s a bit tough to leave my students during the last four weeks of the semester. For both my graduate students and undergraduates, this is “crunch time”. While I left my in-person classes this week in capable hands of a research assistant, it seemed a bit ironic that a group focusing on academic excellence would host the event at this time of year. Now, there might never be a good time, and planning around spring breaks of 400+ institutions will inevitably leave some disappointed. But for me — it is painful.

ISU Industrial Cybersecurity Engineering Technology Program Achieves ABET Accreditation

Seven years ago I left a great job as the Director of Industrial Control Systems Security at FireEye/Mandiant to head up ISU’s Industrial Cybersecurity Degree program.

I did it because I was — and I remain — certain that the best way to secure the digital future for critical infrastructure is to create the high quality educational programming that will give us a new generation of engineering and technology professionals capable of seamlessly moving between IT, OT, engineering, and cybersecurity domains.

Along this journey, I have proposed new educational pathways, recruited students, authored courses, created exams, hired faculty, taught diligently, stayed up past midnight grading, and placed students at fantastic national-level employers.

It has been a stretching experience to essentially start over with nothing but a vision.

About two years ago, ISU’s Industrial Cybersecurity Program received recognition as an NSA-designated cybersecurity program.

I am pleased to share that this week the Program has also received official ABET accreditation!

As a testament to ISU ESTEC’s quality, all five of the department’s Engineering Technology Programs (Electrical, Instrumentation, Mechanical, Nuclear Operations and Industrial Cybersecurity) are ABET accredited!

Webinar: A new generation of industrial cybersecurity professionals

I am pleased to announce the ISAGCA Webinar on building a new generation of industrial cybersecurity professionals this coming Thursday (April 25).

The Webinar will present the current culmination of nearly a five year effort to establish a concensus-based foundation of knowledge that qualifies industrial cybersecurity professionals

Following the webinar, the 125-page document and all the supporting resources will be available on the ISAGCA web site. This will serve as a valuable resource for the entire community. This would not have been possible without collaboration among DOE/INL, ISAGCA and ISU.

On the Webinar, I will discuss the broad needs, methodology and results of the work.

In addition to the “knowledge” document, we are releasing all of the data gathered and analysis performed. Importantly, this documentation includes the self-reported professional and academic qualifications of the participants. This an impressive level of transparency.

In addition, we are preparing an academic article that focuses on methodology and key insights in greater detail.

Here is the link to the Webinar registration. I hope you will join us!

CS4CA Conference Recap

Last week I attended the Cyber Security for Critical Assets conference in Houston. I was impressed. Low key, probably 200 attendees plus reps from 20 vendors. Hight asset owner presence. I loved hearing the hallway conversations — people talking about real challenges and real experiences.

I was surprised by the candor in the technical deep dive sessions: OT security practioners at asset owners talking about how they had built their programs, including what technologies they had selected for what purpose, and what they planned to do next.

I moderated a panel on workforce development. While it seems everyone likes training, ours was the only presentation that dealt specifically with intentional developing your people. Panelists included Nikolai Zlatarev of Castleton Commodities, Jude Ejiobi of University of Houston Downtown, and Chuck Bondurant of the Texas Public Utilities Commission.

It was a great panel, and I appreciated representation from industry, academia, and (quasi) government. Each panelist had a different professional pathway into OT security, and that was a key take away. It is such an interdisciplinary field.

Nikolai emphasized that the best way to develop skills was through real world experience. He liked to throw people all the way in. He explained that his career was one great challenge after another. He was obviously a man who had learn to thrive in ambiguous environments, and has a knack for keeping a positive attitude.

Jude does a good bit of security consulting work, and was brought into academia as a lecturer, but now helps direct the UH Downtown Masters in Security Management. Practical and well-spoken.

Chuck came into OT security when he learned that he wasn’t cut out for retirement after military service. His job involves liaising with and supporting Texas utilities on cybersecurity. When he took the job, he had no idea what a PLC was, but his military cybersecurity experience gave him a solid foundation to build on.

I think there is great value to having candid conversations about developing ourselves and our programs. I will look forward to next year!

Student Research Symposium and Engineering Technicians

Two weeks ago ISU hosted its annual Research and Creative Works Symposium. It is a really neat event that gives any student – graduate or undergraduate – a forum at which to share their work. Students simply sign up and voila they have a speaking spot in front of a panel of judges and anyone who might come support them!

I think this is a very useful, low stakes practice for students.

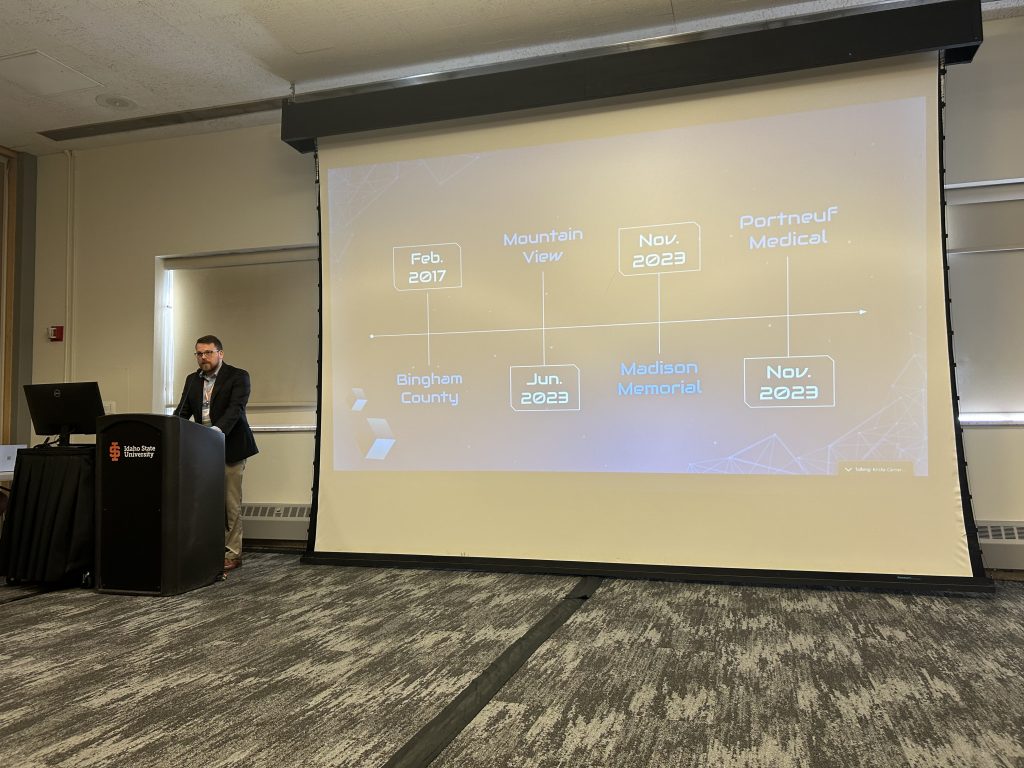

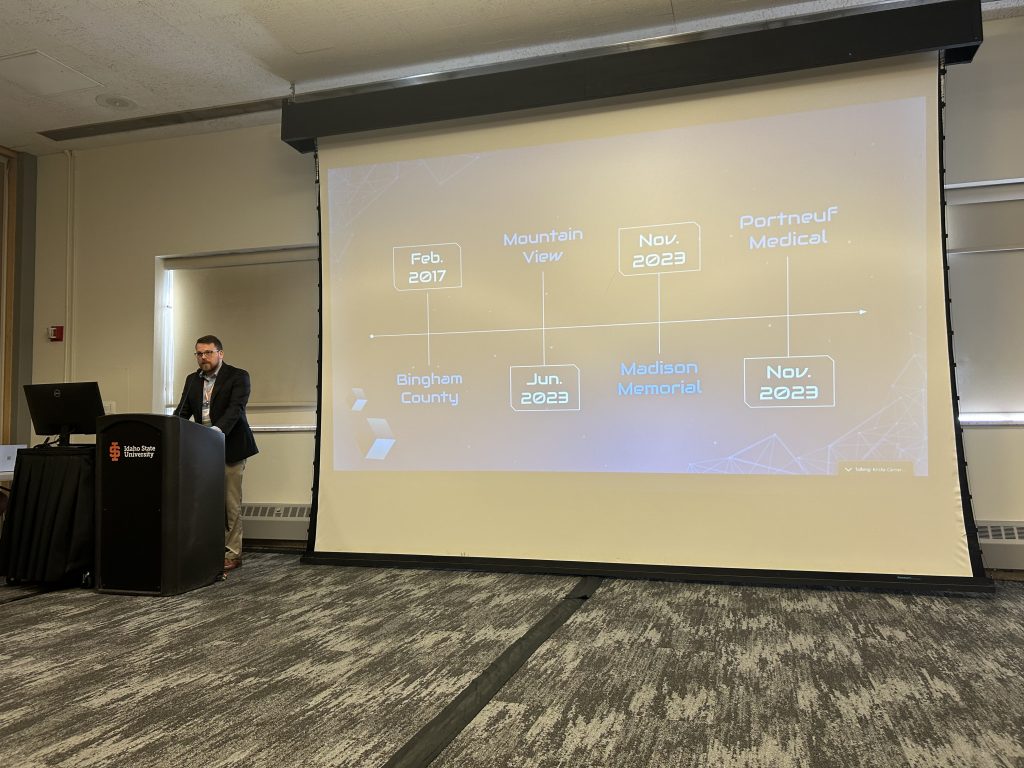

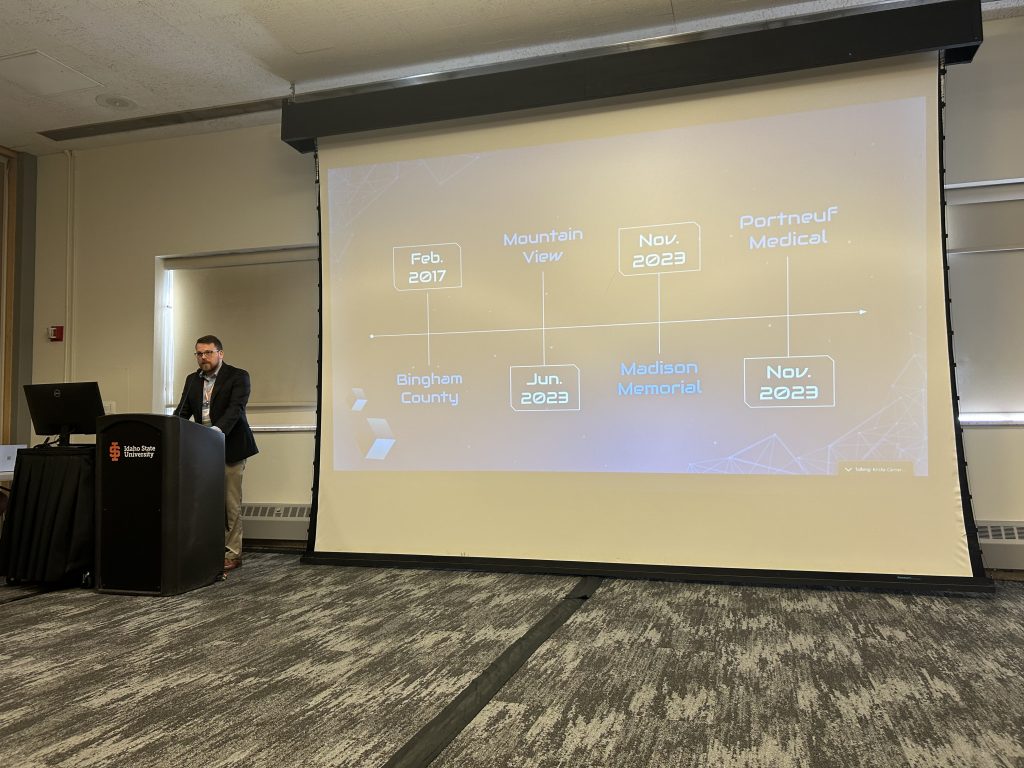

This year I am supervising two graduate student research projects. One, who chose to present at the conference, is investigating the effects of ransomware in Southeast Idaho. A handful of organizations, including local governments, health care, and manufacturing have all taken a ransomware hit. The student’s research is qualitative, relying on interviews with individuals who were impacted. Really insightful to have a collection of first-hand perspectives.

I was so impressed that all my graduate students will be required to present next year!

But that wasn’t what I found the most intriguing. After my student presented, I stuck around to hear other presentations.

I was especially intrigued by research into training levels of psychiatric technicians. Psychiatric care technicians work in mental health facilities and have more regular contact with patients than any other health care provider. They engage in a variety of interventions, including group therapy sessions.

Despite the boots-on-the ground role that these technicians play for patients, in Idaho and 45 other states (if I remember the statistic correctly), there is no baseline education or training requirement for such technicians.

The student had created and administered a questionnaire to a variety of psychiatric care professionals at a local psychiatric hospital to see what level of training psychiatric technicians should have. The student’s research found (again if I remember correctly) that a technician should have between 8 and 40 hours of training related to their role – which training could be concurrent with job function.

When she was finished, another member of the audience (who I surmised was the student’s supervisor) asked “what do you plan on doing next?”

“Well,” the student responded, “In our program we have learned about lobbying. I am going to lobby for change. I think there needs to be a minimum level of training these technicians need to have.”

Ahhh. Now you can see where I am going…

In the OT sphere, in the USA alone, we have probably several hundred thousand technicians – instrumentation and control technicians, electrical engineering technicians, mechanical engineering technicians – who install, configure, operate and maintain industrial control systems – systems that provide electricity, drinking water, and manufactured goods. Not a single state (0 of 50) requires them to have any cybersecurity training or demonstrated competence.

“Wow”, I thought, “We require barbers and hairdressers to have professional licensure in all 50 states. But there are no requirements for those individuals whose job performance directly affects the well being of millions.”

This is an addressable issue. Let’s get on it.

Tech Expo 2024!

The ISU College of Technology hosts an annual technology fair for middle school and high school students from across Southeast Idaho. The event, held in the ICCU Dome, attracts more than 2,000 teens to explore technology careers.

Industrial Cybersecurity has hosted a Tech Expo “booth” for 7 years. During the event, I stand in the thoroughfare and ask the youthful attendees “have you ever hacked a computer? Come on over and we will show you how!”

Not a tough sell.

This year I had several of my current Industrial Cybersecurity students run the booth — coaching the high-schoolers through the exercise. We sit the high-schoolers across from one another and help them create a “secret” file via command line, use a default ssh password to access the other person’s computer, steal the secret, and race to shut off the other person’s computer.

Students who have never thought about this get quite excited. When asked what they learned, some students reply that they didn’t know hacking was so easy.

The event is a whirlwind as the booth stays full for four hours. I would estimate we ran 50 or 60 students through the exercise.

What impressed me most this year, is that when I asked students what they were planning to do after they finished high school, I had three or four tell me “I am going into cybersecurity.” I even had one tell me, “I heard about hackers taking out a power grid. I want to do that.”

With a big smile I was able to tell them, “We are almost full for Fall, but I think there’s still some room. Just call or email, and we will get you signed up!”

PCAST Report on CPS Resilience

I enjoyed reviewing the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (which boasts some big name institutions), “Report to the President” on “Strategy for Cyber-Physical Resilience”.

The Strategy offers a total of 14 recommendations across four categories:

- Establish performance goals

- 1.A Define sector minimum viable operating capabilities and minimum viable

delivery objectives - 1.B Establish and measure leading indicators

- 1.C Commit to radical transparency and stress testing

- 1.A Define sector minimum viable operating capabilities and minimum viable

- Bolster and coordinate research and development

- 2.A Establish a National Critical Infrastructure Observatory

- 2.B Formulate a national plan for cyber-physical resilience research

- 2.C Pursue cross-ARPA coordination

- 2.D Radically increase engagement on international standards

- 2.E Embed content on cyber-physical resilience skills into engineering professions

and education programs

- Break down silos and strengthen government cyber-physical resilience capacity

- 3.A Establish consistent prioritization of critical infrastructure

- 3.B Bolster Sector Risk Management Agencies staffing and capabilities

- 3.C Clarify and strengthen Sector Risk Management Agency authorities

- 3.D Enhance the DHS Cyber Safety Review Board (CSRB)

- Develop greater industry, board, CEO and executive accountability and flexibility

- 4.A Enhance Sector Coordinating Councils

- 4.B Promote supply chain focus and resilience by design

The report provides some context and insight on each of these. I can’t help but comment on 1.A. “Define sector minimum viable operating capabilities and minimum viable delivery objectives”.

I really like this idea because it shifts focus from the system itself (networks, software, process equipment) to the delivery of the critical function (power, water, food, etc). This is a great step in thinking through what matters most.

My observation is that in a highly interconnected world, with global supply chains, setting a scope for performance for an entire sector seems challenging because sectors don’t really “exist”. They are not monoliths. Their value is the service they provide to various users and customers, rather than to themselves.

Consider that the number and size of infrastructure service providers can vary greatly depending on geography. What is the minimum level of electricity or water to sustain quality of life for Southeast Idaho? For the city of Los Angeles? For the state of Texas? So the approach has got to include both sector and geography.

And within those geographies, various organizations rely on infrastructure services. Who should receive those services first?

Then, we have to recognize that sources of communications, energy, food, water, and medicine frequently (most frequently?, almost always?) operate across geographic boundaries — including in some (many?) cases across national boundaries.

Finally, each sector is not truly independent of other sectors. One geo-sector’s minimum viability may depend upon and/or conflict with that of another geo-sector.

I am pleased that the PCAST took up this topic. I am very optimistic about incorporating function-centered thinking. I find intriguing the idea of establishing minimum viable operating capabilities and objectives. However, I remain concerned that administrative constructs based primarily on sectors and geographies leave significant gaps.

There are some words in the strategy, such as “enhance supply chain focus” and “enhance cross-sector coordinating councils” that could address this concern, but I found this presented as “do this too” rather than as an indispensable component of CPS robustness and resiliency.

I am not advocating abandonment of sector and geography thinking, but I believe we will need some additional paradigms and/or alternative perspectives to do this well.